Debates on German Leitkultur and Multiculturalism

Author: Dr. Ayse Tecmen, ERC PRIME Youth Project Post-doc Researcher, European Institute, İstanbul Bilgi University

Editor’s note: This blog entry is based on the review of the literature on migration, integration, and citizenship in Germany, which is a part of the country-reports that will be published on https://bpy.bilgi.edu.tr/en/ . Unlike conventional blog entries, these posts aim to inform our readers of the current state of affairs in Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands while conveying how the PRIME Youth project will contribute to the extant literature. Ayhan Kaya

Leitkultur is a concept, which resurfaces in the literature on migration and integration in Germany on a regular basis. Nonetheless, its definition and significance has changed over time. The concept of ‘European Leitkultur’ (leading culture, or guiding culture) was first constructed by political scientist Bassam Tibi in 1998. Tibi argued that Germany should reposition itself at the democratic heart of this modern and enlightened Europe by acknowledging and accepting ‘European Leitkultur’, which refers to the generation of a set of European core norms and values to be accepted and followed by every person living in Germany – indigenous or non-indigenous. Bassam Tibi “denounced multiculturalism as merely an expression of bad conscience over what happened in the colonial era. Germans are additionally plagued by the guilt of the Holocaust, which is why they have been disproportionately tolerant towards immigrants” (Pautz, 2005: 43).[i] While Tibi’s conception of Leitkultur is highly challenging for migrant communities, it still remains a significant part of the discussions on German identity.

By the end of 2000, increases in the number of naturalisation applications and naturalisation of “foreigners” led to a public debate about a common German Leitkultur. In the German context, conservative politician Friedrich Merz who was the then chair of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) in the German Federal Parliament initiated this debate by demanding that immigrants adapt to the German culture if they wanted to stay in the country. This initiated an intense debate on German multiculturality, which followed the Netherlands’ controversial debate about the pros and cons of Dutch multiculturality, which was labelled as the ‘multicultural drama’ (cf. Prins 2002; Duyvendak and Scholten, 2012). [ii] Deploying Tibi’s conception of Leitkultur, Merz redefined Leitkultur as ‘the putative essence of national culture to which immigrants must assimilate’ (Cheesman, 2004: 84; see also Cheesman, 2002). In his propagation of a ‘liberal German Leitkultur’, Merz nationalised and culturalised the concept, suggesting that these core norms and values are (to be) rooted in (a superior) German culture. His provocative statements aimed to regain their lost hegemony in the political field of migration and to recharge the discursively contested theme of the nation (Manz, 2004).

Leitkultur has gained increasing significance and has come to indicate the controversy around the future of the German multicultural society. This controversial debate “which discredited any debate about multiculturalism and tried to replace it - can be perceived as an expression of a certain fear of losing cultural hegemony within the newly declared country of immigration and an attempt to sustain a vanishing homogeneity” (Wilpert, 2013: 118). In fact, it was in the wake of a discussion about foreigners in German society that, for example, the radio station Deutschlandradio broadcast a series under the title ‘Was ist deutsch?’ [What is German?], and the daily newspaper Die Welt published a series of articles under the same title (Die Welt, 23 December 2000 cited in Manz 483). In this sense, the German “self” articulated in the Leitkultur discourse heavily relied on the construction of the non-German “other”. Inadvertently, this led the Turkish minority in Germany to remain marginalized and separated by cultural and religious lifestyles within the Leitkultur discourse. Mueller (2006: 432) articulates this situation as a “parallel society” reinforced by discrimination, xenophobia, limited schooling and low socio-economic status. For the same reason, scholars also argue that this assimilationist discourse is a dialectical process of identity construction in which native-born Germans and immigrants from Turkey construct their respective ‘other’. In turn, the rejection of the Leitkultur by Turkish minorities is also a response to the larger political and social discourse, which contests their belonging (Ehrkamp, 2006).

One of the most significant developments in 2010 was Merkel’s speech noting that multiculturalism had ‘utterly failed’ (cf. Schrader, 2010; Malik, 2015). Even though critics claim that to this day the normative discourse lacks a definition of what is meant by “Leitkultur” and how it is practiced correctly, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU explained it in their 2010 Party congress resolution:

In this way, Germany is more than a country of birth or a residence. Germany is our spiritual home (‘Heimat’) and part of our identity. Our cultural values - influenced by our origin in the ancient world, the Jewish-Christian tradition, enlightenment, and historical experiences - are the foundations for societal cohesion and, additionally, shape the leading culture in Germany, to which the CDU especially feels obligated. We expect that those who join us will both respect and acknowledge this (CDU, 2010: 2 cited in Scherr, 2013: 7).

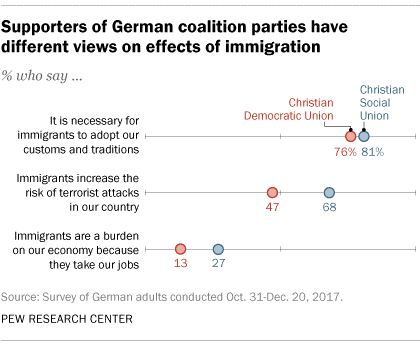

In this sense, German Leitkultur is an attempt to create a model that anticipated socio-economic and socio-cultural adaptation to society in order to be recognized and accepted. This assimilationist approach inevitably isolates and marginalizes migrant and migrant-origin communities. Furthermore, Chancellor Merkel indicated that it would not be enough to offer migrants educational success and access to the labour market, and that participation and assimilation to the dominant German Leitkultur is a necessity. Simultaneously, the society regardless of their political affiliation still remains skeptical about migration and continues the Leitkultur discourse. According to a survey conducted among 1,983 German adults in late-2017 both CDU (76%) and CSU (81%) adherents believe it is necessary for immigrants to adopt German customs and traditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Supporters of German coalition parties have different views on the effects of immigration

Source: PEW Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/21/differing-views-of-immigrants-pose-a-test-for-germanys-coalition-government/ft_18-06-21_cdu-v-csu-views-on-immigrants-2/

* * *

As the literature indicates, Tibi’s conception of Leitkultur connotes a hegemonic cultural identity framework that does not recognize the cultural diversity in Europe in general and Germany in particular. Leitkultur discourse is especially problematic for Turkish-origin immigrants in Germany, most of whom are second or third-generation migrants. The maintenance of this debate by key political and academic figures over the years is controversial as it promotes assimilation rather than intercultural dialogue. The construction of hegemonic identity, and the resulting dominant cultural expectations have significant consequences for both the host community and the migrant-origin community. Tibi’s approach to culture and identity, as well as the resulting political and public debates, perpetuate the isolation and marginalisation of Turkish-origin migrants, which lead to humiliation, isolation, and deprivation. As we argue in the ERC-funded PRIME Youth Project, this is a critical juncture in socio-cultural dynamics that leads to extremism and radicalisation among the Muslim-origin Turkish youngsters. However, as the co-radicalisation literature indicates, marginalisation is not exclusive to Muslim-origin youngsters. As such anti-immigrant views, which are also perpetuated by the Leitkultur debate among the native youth, are also a symptom of radicalisation among native youth in Germany and Europe in general.

[i] For a thorough discussion on multiculturalism, in brief, multiculturalism refers to a society that contains several cultural or ethnic groups in which cultural groups do not necessarily engage with each other. Multiculturalism assumes that cultures are primordial, distinct, separate, fixed, static, pure wholes, which have the risk of being polluted, degenerated and distorted when they interact. This assumption is actually a continuation of the 19th-century notion of culture. This understanding is an ethnocentric one, which inevitably leads to a kind of hierarchy between cultures. For further information, see Kymlicka (2012); Beck, and Grande (2007); Kaya (2012); and Brahm Levey (2012).

[ii] For studies on other European countries with a similar approach to integration, see Alba and Nee, 2009; Brubaker, 2001, Ehrkamp, 2006; Ramm, 2010; Scholten et al 2017.

References

Alba, R.D. and Nee VG (2005). Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

Beck, Ulrich and Edgar Grande (2007). “Cosmopolitanism: Europe’s Way Out of Crisis.” European Journal of Social Theory 10 (1) (2007): 67-85.

Brubaker, R. (2001). The return of assimilation? Changing perspectives on immigration and its sequels in France, Germany, and the United States. Ethnic and Racial Studies 24(4): 531–548. Cheesman, T. (2002).

Akçam–Zaimoğlu–‘Kanak Attak’: Turkish Lives and Letters in German. German Life and Letters, 55(2), 180-195.

Cheesman, T. (2004). Talking" Kanak": Zaimoğlu contra Leitkultur. New German Critique, (92), 82-99.

Duyvendak, J. W., & Scholten, P. (2012). Deconstructing the Dutch multicultural model: A frame perspective on Dutch immigrant integration policymaking. Comparative European Politics, 10(3), 266-282.

Ehrkamp, P. (2006). “We Turks are no Germans”: assimilation discourses and the dialectical construction of identities in Germany. Environment and Planning A, 38(9), 1673-1692.

Geoffrey Brahm Levey (2012). Interculturalism vs. Multiculturalism: A Distinction without a Difference?, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33:2, 217-224. Kaya, A. (2012). Islam, Migration and Integration: The Age of Securitization. London: Palgrave.

Kymlicka, W. (2012). Multiculturalism: Success, failure, and the future. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Malik, K. (2015). The failure of multiculturalism: Community versus society in Europe. Foreign Affairs, 94, 21-33.

Manz, S. (2004). Constructing a Normative National Identity: The Leitkultur Debate in Germany, 2000/2001, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 25:5-6, 481-496, DOI: 10.1080/01434630408668920

Mueller, C. (2006). Integrating Turkish communities: a German dilemma. Population research and policy review, 25(5-6), 419-441. Pautz, H. (2005). The politics of identity in Germany: the Leitkultur debate. Race & Class, 46(4), 39-52.

Pew Research Center (2017) Fall 2017 Survey, Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/FT_18.06.21_Germany_Politics_Topline.pdf [Retrieved: 16 December 2019]

Prins, B. (2002). The nerve to break taboos: New realism in the Dutch discourse on multiculturalism. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l'integration et de la migration internationale, 3(3-4), 363-379.

Ramm, C. (2010). The Muslim makers: how Germany ‘islamizes’ Turkish immigrants. Interventions, 12(2), 183-197.

Scherr, A. (2013). The construction of national identity in Germany: “Migration Background” as a political and scientific category. Toronto: RCIS Working Paper, (2013/2).

Scholten, P., Collett, E., Perovic M. (2017). “Mainstreaming migrant integration? A critical analysis of a new trend in integration governance”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(2) 283–302.

Schrader, M. (2010). “Merkel Erklärt ‘Multikulti’ Für Gescheitert”, 16.10.2010. DW.COM, 2010, www.dw.com/de/merkel-erklaert-multikulti-fuer-gescheitert/a-6118143 [Retrieved: 17 December 2019]

Wilpert, C. (2013). “Identity issues in the history of the post-war migration from Turkey to Germany”, German Politics and Society, Issue 107 31 (2), 108–131.