Sometimes Anger may be the Best Counsellor: Understanding the New Global Wave of Protests

Author: Prof. Emre Erdoğan, İstanbul Bilgi University

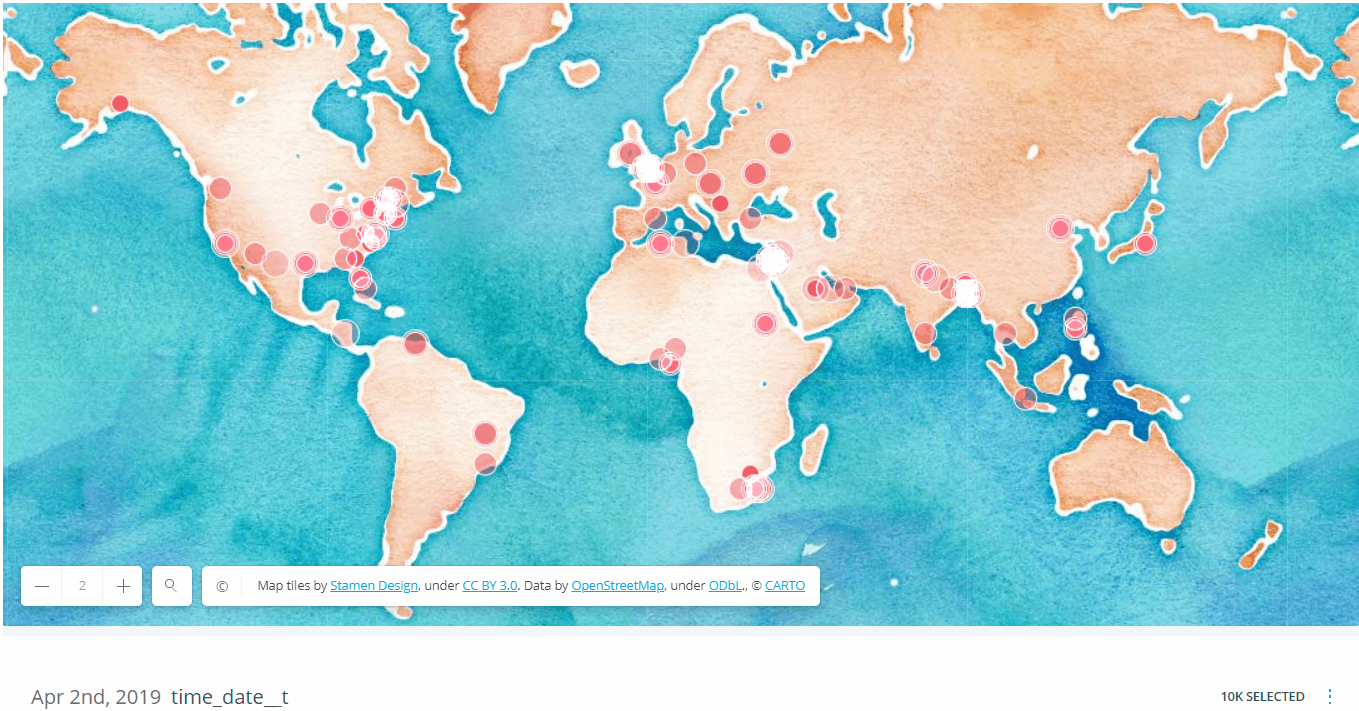

A spectre is haunting the World. Ten years after the Arab Springs, the protest movements became widely observable across the World, from Lebanon to Chile, from Hong to Catalonia. It is unknown whether these protests are signals of the revival of the contagious revolutions of 1848, 1968 or 2011, but they deserve special attention from those who are interested in the analysis of social movements.

The journalistic accounts forwarded many explanations for this global new wave of protests. First, economic inequalities between and within societies are the usual suspects for triggering public protests. Globalization did not improve the living conditions of many and it did not help to reduce inequalities. Similar to the period before the French revolutions, the rising expectations of the new generations have not been satisfied yet, and this led to a widespread dissatisfaction among younger citizens (Chile and Lebanon). A second explanation is related with demands for political, civil and private liberties. Younger generations reacted to increased control of the government on their political liberties (Hong Kong), civil rights (Indonesia) and private lives (Indonesia). In the Catalan case, protesters reacted to the decision of the Supreme Court to prison eight separatist leaders. Third, climate change became an issue owned by the new generation and led to a series of protests in the capitals of the developing world (Canada, UK and Australia). At first sight, these events may be perceived as independent from each other, but a small review of the literature about protest movements can show us the hidden link between them.

Fifty years-long study of protest movement showed that collective grievances, especially in the material domain pushed citizens to participate in protest movements. However, with time, we also learned that grievances are not limited to relative material deprivation; comparison of one’s material situation with his expected life conditions. Contributions of scholars of protest movements first showed that collective grievances are more important than individual ones. Secondly, deprivation feelings are not limited to the material domain; whenever an individual does not receive what he believes he deserves; it turns out to be a strong feeling of injustice. This conception is not limited to distributional justice, but also it covers the concept of procedural justice; the fairness of decision-making procedures and the relational aspects of the social process. These grievances -individual/collective, material/non-material- are transformed into a powerful feeling: Anger.

Anger is an emotion directly related to unfairness; it seeks people to seek justice and retribution and demand for compensation. Recent studies show that individuals became more risk-averse, they undermine possible negative consequences of their actions. In the context of protest movements, anger has been indicated as the most important emotion motivating individuals to participate in mass protests. These findings are not limited to the protest movements of the first world. Pearlman showed that anger drove Arab citizens to join mass protests and undermine the deadly consequences of their actions. Erişen’s findings were confirming the hypothesis that anger was pushing individuals to protest movements such as the Gezi Protests. These experimental results are confirming my qualitative findings that anger was the dominant feeling of the participants of the Gezi Protests.

All these discussions give us the answer we are looking for: Anger may be the link between these different protest movements across the globe. Economic inequalities, restrictions put on civil, political and private liberties, and ignoring Climate Change are the indications of the same malady, unfairness. It is clear that economic inequalities are materialized in widening relative deprivation of youngsters and societal unfairness. Meanwhile, the patronage of older politicians on the opportunity spaces of young people’s civil, political and private lives is another example of unfairness. Finally, the negative consequences of Climate Change and the unwillingness of the politicians to take measures against this global phenomenon attracted the anger of the younger ones, crystallized in the words of Greta Thunberg.

All these unfair attitudes of the politicians of today are transformed first to a collective feeling of anger, and then to the global contagion of mass protests. Today, politicians are looking for policies to solve this global discontent. For example, the president of Chile responded to protesters with a cabinet reshuffle and widening social policies. The Lebanese government launched an agenda of economic or political reforms and the demands of the protestors of Hong-Kong are not responded yet. However, all these reactions seem to be concentrated on the distributional justice side of the problem -though they will fall short- and the demands for procedural justice are not discussed. And, there is no global initiative to solve the Climate Change problem. The typical reaction of old-style politicians is not more than giving short term promises and it is clear that this strategy won’t work unless there is a consensus to develop inclusive mechanisms for the most vulnerable ones, the new generation in the current case.

For an alternative version of this blog post with links to relevant articles please see the document below.