The Spots to Visit in a “No-Go-Zone”: Notes on the problems and proposals in Molenbeek

Metin Koca, ERC PRIME Youth Project Post-Doc Researcher, European Institute, Istanbul Bilgi University

March 29, 2022

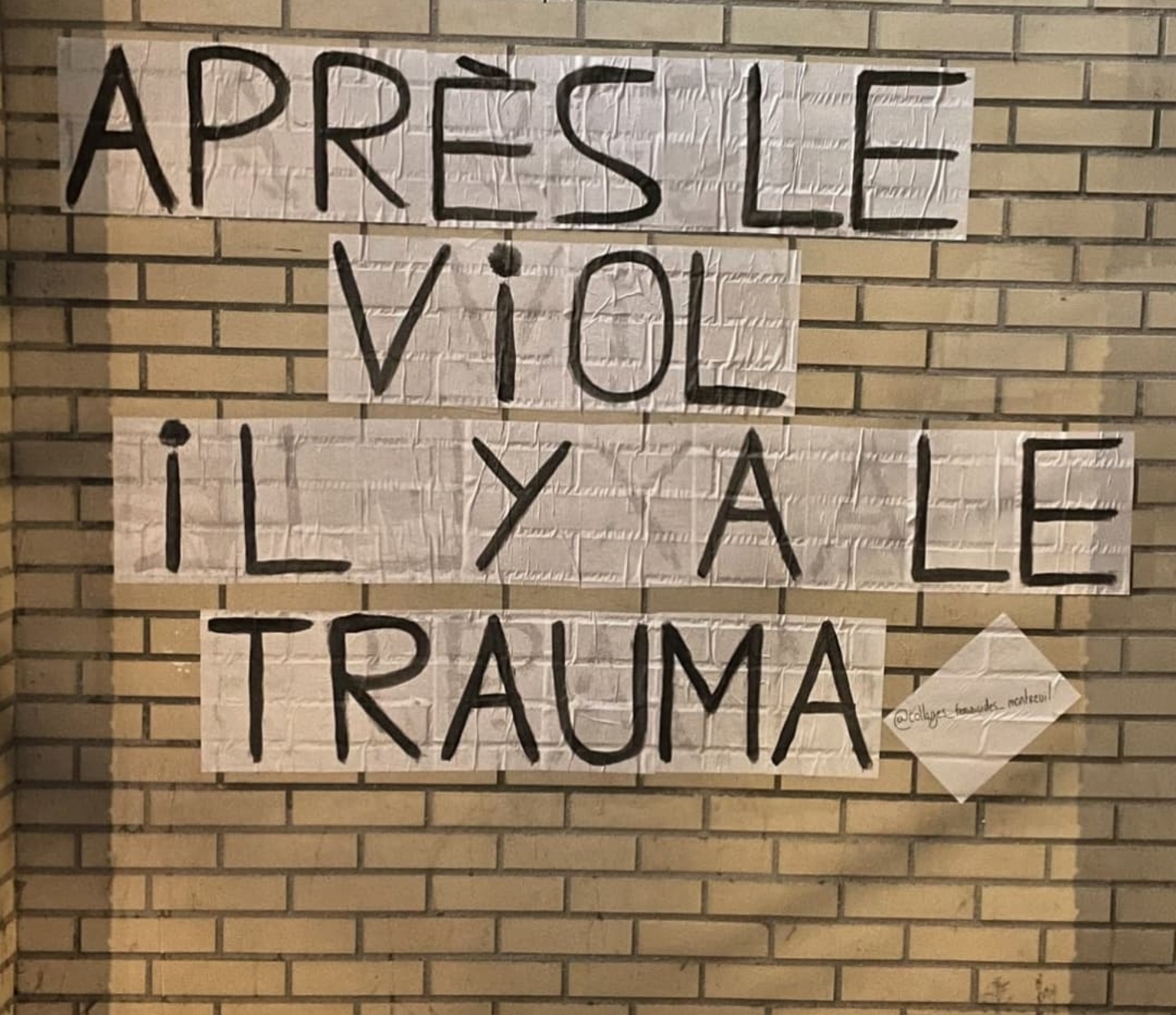

The posters about housing rights, some rowdy lads keeping the street corners, artists who reconnect the town with what lies beyond, and civil society organizations trying to translate the local problems into country-level proposals… These were what my eyes caught in a short field trip, intended for me to breathe the air in a few neighborhoods that represent the “no-go-zones” of Europe. To me, these zones are not for others to avoid. Instead, the term signifies a zone to which others do not pay attention until the crisis hits them. “Their crisis, our misery” (fr. leur crise, notre misère) on a poster summarized these zones well. Indeed, Marxists erase the misery and write “revolution” (fr. révolte), whereas Islamists write “Jihad.” Starting with the Canal bank in the municipality of Molenbeek, others tried to pave the way for new kinds of hybridity in response to the terror attacks in 2015 and 2016. This blog post is based on my impressions of a humble three-day trip to Molenbeek in the light of the PRIME Youth interviews. My aim is to touch upon the recent efforts to resolve youth unemployment, cultural barriers, and related social challenges (e.g., housing, education, delinquency, pollution).

Among my destinations were the Northeastern banlieues of Paris, Villepinte and Montreuil, and the two municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region, Schaerbeek and Molenbeek. Villepinte is the commune where Eric Zemmour addressed Muslims in front of the angry faces of locals and the organizations such as Antifa and SOS-Racisme.[i] Not far from it, there is a highly populated banlieue called Montreuil-sous-Bois. Specific groups in Montreuil, ethnically defined before all else, are speculated to have nurtured new sectes—e.g., radical Muslims or Jehova’s witnesses.[ii]

The debate is essentially the same in Belgium: conquest and reconquest have become its keywords. Within walking distance of one another, Molenbeek and Schaerbeek are as close to the French political landscape as it is to the European Commission in Brussels. Molenbeek is arguably the most remarkable and famous due to its well-mediatized reputation as the haven of violent extremists who targeted Brussels and Paris. In 2015, Belgium’s home affairs minister declared that the government did not “have control of the situation in Molenbeek.”[iii] So there is a reason that even our interlocutors from Germany and the Netherlands have a clear opinion: “Molenbeek in Belgium is not Belgium.”[iv] Accordingly, the municipality provided the manpower for ISIS in Europe, whereas its more diverse neighbor, Schaerbeek, was where the bombs were made for the attacks.[v] Their fame territorializes a long-standing controversy about the distance between hearts in Europe. The homeless people I saw in front of the Immigration Office at the border of Molenbeek, Boulevard du Neuvième de Ligne, must be among the indicators of this affective social distance.

According to the Brussels Institute of Statistics and Analysis (BISA), Molenbeek is miles away from the rest of Belgium in terms of economic standards. Nearly a year before the rise of ISIS, in 2012, youth unemployment (<25) was above 40%, compared with the national average of 20%.[vi] In 2018, the general unemployment rate was above 30% in the municipality, around 9% in the rest of the country.[vii] “Only the jobs that the Whites no longer like to do are available to us,” said a Moroccan-origin Muslim interlocutor of the PRIME Youth from Belgium.[viii] Referring to Molenbeek, Schaerbeek, and Borgerhout, he associated this socioeconomic struggle with the negative image of the Molenbeek youths: “We did not have an equal start with all other kids. We need more support instead of being confronted with negative representations.”[ix] Under the watchful eyes of the authorities, they write on the walls: “there is no liberty under surveillance” (fr. il ñ'y a pas de liberté sous surveillance). Meanwhile, initiatives such as MolenGeek encourage school dropouts not to lose their future optimism.[x]

Académie Jeunesse Molenbeek (ACJM) has grown to be one of the most influential initiatives to keep unemployed youths from social isolation and lawbreaking. I brought from Istanbul the Galatasaray goalkeepers’ green jersey to match the colors of ACJM. As I expected, I came across many prospective football players in the 1-kilometer between Rue du Jardinier and the Avenue du Sippelberg, where the stadium is located. The former mayor of Molenbeek supported the team with the argument that the “sport […] motivate[s] [youths][…], helps tackle delinquency, and brings prestige to an individual.”[xi] The Athletic Club was established to respond to the discrimination against Muslims by other teams,[xii] including the First Division B team R.W.D. Molenbeek, some have argued.

Over time, the youth academy has distinguished itself, emphasizing the local and Muslim players. It has managed to give many youngsters an occupation to be passionate about. However, their ardent sense of belonging does not seem to have created a definitive solution to social polarization, given that the families of the players in other teams are uneasy about sending their children to the match as if they are sending them to war.[xiii] A non-sectarian alternative would first require the R.W.D. Molenbeek to build infrastructure for the local youths. The ACJM will remain a haven for the local Muslim players until that happens.

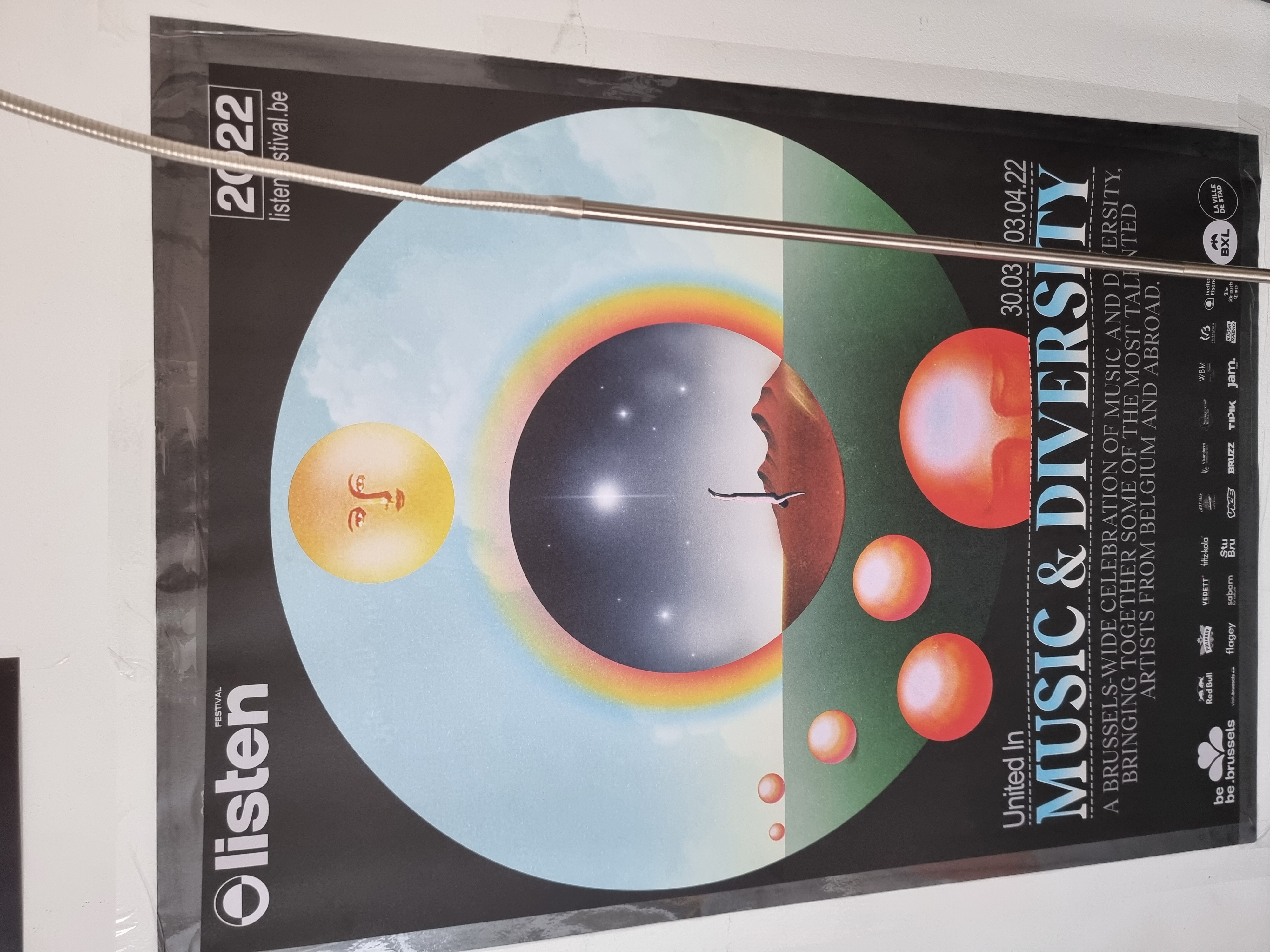

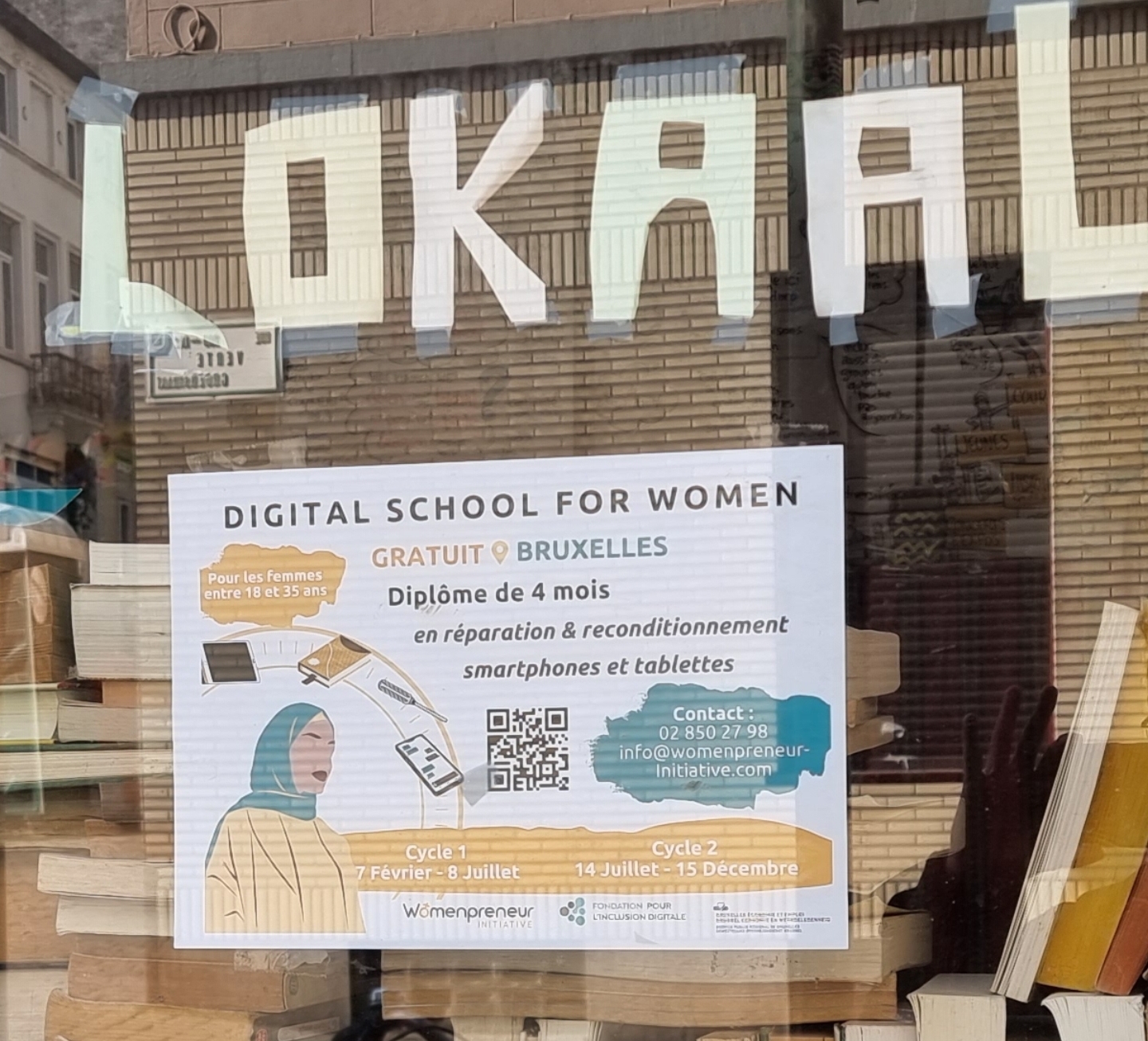

Numerous civil society organizations settled in Molenbeek to turn narrow-minded communitarianism into a cultural link without being assimilationist. They have peace with the Moroccan cuisine cafes, halal butchers, and covered women, but they think through them and encourage the locals to join the thought process. The House of Cultures and Social Cohesion of Molenbeek (fr. Maison des Cultures et de la Cohésion Sociale de Molenbeek) is a creative public service space with workshops and exhibitions organized for adults and children. The Wallonia-Brussels Federation (fr. Fédération Wallonie Bruxelles) is also present in the municipality with a claim to support artistic creation and expression in the French language. Foyer is a youth center that services migrant pupils and newcomers who do not speak the local languages. From Raphaël Cruyt to the Noorsen Collective, many local artists are behind the activities of these organizations. With the establishment of the Millennium Iconoclast Museum of Art (MIMA) and La Vallée Molenbeek, there are obvious signs of gentrification in the Canal section. Recalling the near past, Fatima (24), a PRIME Youth interlocutor from Molenbeek, evaluates the change: “That area was really a residential area, there were no shops or restaurants, so it had many shortcomings.”[xiv]

Conclusion

The no-go-zones in Europe deserve more attention. Their rigid local identities help the residents make sense of a collective loss. “This is where you always feel fine,” a PRIME Youth interlocutor tells about Molenbeek, Schaerbeek, Anderlecht, and St Joost as opposed to the Brussels city center, where “you may encounter people acting weird and racist.”[xv] Another Muslim interlocutor from Uccle, a neighboring municipality in the Brussels-Capital Region, explains how her family faced “a lot of racism” in “this very white and rich” neighborhood. In comparison, she argues, others in Molenbeek “did not experience that much trouble.”[xvi] Some of our Muslim interlocutors are not very happy to stay in Molenbeek, but they have to: “I’d [rather] go back to Puurs or St Amands where there is more nature and peace.”[xvii] Despite the obstacles, Fatima concludes that the local youths should not sit and wait for their fates to change suddenly:

What does it mean to feel welcome?

You have to make sure that you are welcome.

You need to do what you need to do.

I had to learn Dutch and do my best.

You should not wait for the feeling that you are welcome.

You have to make this happen yourself.”[xviii]

-------

[i] William Audureau, Arthur Carpentier, and Adrien Sénécat, “Eric Zemmour à Villepinte : Ce Que Les Images Montrent Des Violences à Son Meeting,” Le Monde.Fr, December 10, 2021, https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2021/12/10/ce-que-les-images-montrent-des-violences-au-meeting-d-eric-zemmour-a-villepinte_6105568_4355770.html.

[ii] Sophie Taylor and Laure Bretton, “France Expels ‘Radical’ Cleric in Anti-Crime Drive,” Reuters, August 19, 2010, sec. World News, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-imam-deportation-idUSTRE67I3FY20100819. Susan Palmer, The New Heretics of France: Minority Religions, La Republique, and the Government-Sponsored “‘War on Sects’” (Oxford University Press, 2011), pp18-28.

[iii] Kimiko De Freytas-Tamura and Milan Schreuer, “Belgian Minister Says Government Lacks Control Over Neighborhood Linked to Terror Plots,” The New York Times, November 15, 2015, sec. world, https://www.nytimes.com/live/paris-attacks-live-updates/belgium-doesnt-have-control-over-molenbeek-interior-minister-says/.

[iv] PRIME Youth Interview, 4 October 2020.

PRIME Youth Interview, 17 May 2021.

[v] Christina Capatides, “Molenbeek and Schaerbeek: A Tale of Two Tragedies,” CBS News, April 11, 2016, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/molenbeek-and-schaerbeek-brussels-belgium-a-tale-of-two-terror-tragedies/. [vi] “Map Statistics - Youth Unemployment Rate in the Brussels Region,” accessed March 28, 2022, https://monitoringdesquartiers.brussels/maps/statistiques-marche-du-travail-bruxelles/chomage-region-bruxelloise/taux-de-chomage-des-jeunes/1/2018/.

[vii] “Map Statistics - Unemployment Rate in the Brussels Region,” accessed March 28, 2022, https://monitoringdesquartiers.brussels/maps/statistiques-marche-du-travail-bruxelles/chomage-region-bruxelloise/taux-de-chomage/1/2012/.

[viii] PRIME Youth Interview, 6 October 2021.

[ix] PRIME Youth Interview, 6 October 2021.

[x] Eanna Kelly, “MolenGeek: The Dropout-Founded Coding School That Has Tech Moguls and Royalty Buzzing,” Sifted, July 6, 2021, https://sifted.eu/articles/ibrahim-ouassari-molengeek/.

[xi] Vivek Chaudhary, “How Molenbeek Fought Back against Isis – with Football,” The Guardian, October 30, 2016, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/29/molenbeek-brussels-fighting-isis-football.

[xii] Alexandre D’hoore, “The Renaissance of Molenbeek,” The Brussels Times, February 19, 2018, https://www.brusselstimes.com/46544/the-renaissance-of-molenbeek.

[xiii] “‘Je n’envoie Pas Mes Enfants à La Guerre’: Le FC Stockel (U19) Fait Appel à La Police Pour Son Match Du Week-End Contre l’Académie Jeunesse Molenbeek,” DH Les Sports +, February 14, 2022, https://www.dhnet.be/regions/bruxelles/le-fc-stockel-u19-fait-appel-a-la-police-pour-son-match-du-week-end-contre-l-academie-jeunesse-molenbeek-620a3c389978e2539894e2e2.

[xiv] PRIME Youth Interview, 25 May 2021.

[xv] PRIME Youth Interview, 19 October 2020.

[xvi] PRIME Youth Interview, 25 November 2020.

[xvii] PRIME Youth Interview, 28 October 2020.

[xviii] PRIME Youth Interview, 25 May 2021.