The Transnationalized Social Question: Migration and Social Inequalities

Author: Prof. Thomas Faist, Bielefeld University, Department of Sociology, Center on Migration, Citizenship and Development (COMCAD)

On a global scale, distress and social instability today are reminiscent of the living conditions that prevailed through a large part of the nineteenth century in Europe. At that time, the social question was the central subject of volatile political conflicts between the ruling classes and working-class movements. From the late nineteenth century onward, the social question was nationalized in the welfare states of the global North which sought a class compromise via redistribution of goods, whereas social protection beyond the national welfare state is found mostly in soft law in the form of social standards. We now may be on the verge of a new social conflict, again on a transnational scale, but characterized more than ever by manifold boundaries—such as those between capital and labour, North and South, developed and underdeveloped or developing countries, or those in favour of increased globalization against those advocating national solutions.

The contemporary social question is located at the interstices between the global South and the global North and also revolves around cultural heterogeneities. A proliferation of political groupings and NGOs rally across national borders in support of various campaigns such as environmental concerns, human rights, and women’s issues, Christian, Hindu, or Islamic fundamentalism, migration, and food sovereignty, but also resistance to growing cultural diversity and increasing mobility of goods, services, and persons across the borders of national states. The nexus of South–North migration and cultural conflicts is no coincidence, as cross-border migration from South to North not only raises economic issues such as productivity and labour market segmentation but also has been part of the constitution of cultural conflicts around “us” vs. “them”. Migration thus has been one of the central fields in which the solution of the old social question in the frame of the national welfare state has been called into question, hence the term “transnationalized social question”. One of the core questions for the social sciences therefore is: how is cross-border migration constituted as the social question of our times? One of the sub-questions reads: how are class and cultural conflicts constituted in the processes of post-migration in immigration and emigration states?

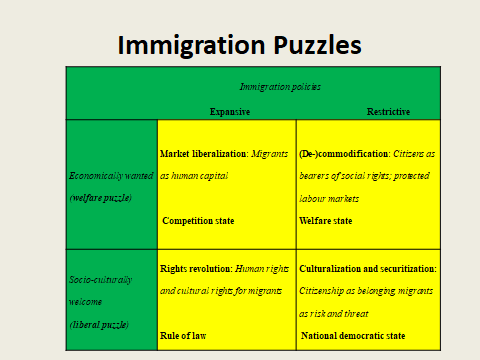

The politics of social inequalities in immigration states: politics around migration and inequalities runs along two major lines, economic divisions and cultural ones (Figure 1). With respect to economic divisions, they lie between market liberalization in the competition state and the de-commodification of labour as part of the welfare paradox: economic openness toward capital transfer is in tension with political closure toward migrants. It is the dichotomy of the competition state vs. the welfare state. In the cultural realm, the contention occurs over the rights revolution vs. the myth of national-cultural homogeneity. It finds expression in the liberal paradox, the extension of human rights to migrants who reside in welfare states against the efforts to control borders and cultural boundaries. It is the juxtaposition of the rule of law vs. culturalization and securitization. Above all threat perceptions often lead to a culturalization of migrants (e.g. viewing lower-class labour migrants as unfit for liberal and democratic attitudes), and to an overall securitization of migration (e.g. seeing migrants as prone to commit violent crimes). It is a juxtaposition of the multicultural state and the rule of law on the one hand and the democratic-national state on the other hand. Economic divisions along class lines structure the politicization of cultural heterogeneities.

The welfare paradox (market liberalization and the welfare state) and the liberal paradox (securitization and the rights revolution) have formed patterns that constitute the main pillars of the dynamics of the politics of (in)equalities and integration. In sum, market liberalization serves as a basis for class distinctions among migrants, or at least reinforces them, while securitization culturalizes them. Over the past few decades, the grounds for the legitimization of inequalities have shifted. Ascriptive traits have been complemented by the alleged cultural dispositions of immigrants and the conviction that immigrants as individuals are responsible for their own fate. Such categorizations start by distinguishing legitimate refugees from non-legitimate forced migrants. Another important trope is the alleged illiberal predispositions of migrants and their inadaptability to modernity. Bringing together market liberalization and culturalized securitization, the current results could be read as Max Weber‘s Protestant Ethic reloaded: politics and policies seem to reward specific types of migrants, exclude the low- and non-performers in the market and the traditionalists, and reward those who perform well and espouse liberal attitudes. In brief, it is a process of categorizing migrants into useful or dispensable.

These processes have not simply led to a displacement of class by status politics. After all, class politics is also built along cultural boundaries, such as working-class culture, or bourgeois culture. Nonetheless, the heterogeneities that are politicized in the contemporary period have somewhat shifted: cultural heterogeneities now stand at the forefront of debate and contention. What can be observed is a trend toward both a de-politicized and a politicized development of heterogeneities in European public spheres. As to trends toward de-politicization, multicultural group rights, in particular, have been contentious and criticized as divisive. Over time, multicultural language has been replaced by a semantic of diversity or even super-diversity in market-liberal thinking and a semantic of threat in nationalist-populist rhetoric. Given this background, it is possible that market liberalization has also contributed to the decline of a rights-based approach and the rise of a resource-based approach. With specific regard to culture, we have seen a shift in policies from group rights to individual resources which can be tapped by enterprises. Diversity, at least in the private sector, mobilizes the private resources of minority individuals and looks for their most efficient allocation for profit- and rent-seeking. It is somewhat different in the public sector, especially in the realm of policing but also in the education and health sectors, in which service-providers seek more efficient ways of serving the public. In general, what we find is a seminal shift from a rights-based to a resource-based approach in dealing with cultural difference. Incidentally, this can be observed in the transnational realm as well. For example, the World Bank has for years propagated a resource-based approach to link migration to development in casting migrants as development agents of their countries of origin through financial remittances.

While a partial de-politicization of cultural heterogeneities through diversity management may help to achieve partial equalities in organizations, multicultural policies are inextricably linked to national projects. After all, such policies are meant to foster national integration and the social integration of immigrants as minorities into national life. From all we know, migration, migrants, and these policies are therefore likely to remain the chief target of securitizing and xenophobic efforts. While the rhetorical criticism of multiculturalism is ever mounting, existing multicultural policies are not reversed to the same extent. Quite to the contrary: the political struggle is ongoing.